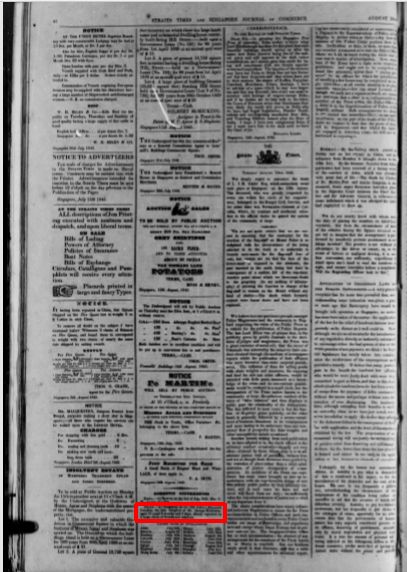

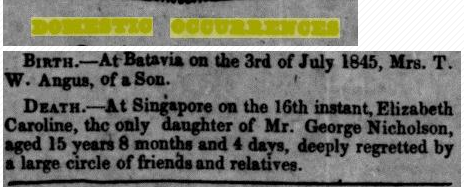

Did you know that Singapore published obituaries in the newspapers as early as 1845?

Did you know that Singapore had published obituaries in the newspapers as early as 1845? Here’s an example available at the archives in the Information Resource Centre in Singapore Press Holdings.

Newspaper obituaries serve as a public record of people who have died in the community.

Before the widespread use of smartphones, social media and chat apps, the print obituary was the fastest way to tell friends and acquaintances about the passing of your family member.

Being an announcement, the print obituary served a primarily functional purpose for informing readers of a person’s death. It was composed of text that included the deceased’s name, date of death and who his family members were. A picture of the deceased, in a standard portrait size, was quite a ubiquitous feature of the printed column. Ordinary families were prudent with their layout of text keeping white space as minimal as possible, but when Singaporeans became wealthier in the later 90s, the obituaries that were published reflected their willingness to spend.

Besides obituaries, Singaporeans also used papers to pay tribute to the dead and thank well-wishers with memoriam ads and acknowledgements. When wealthy businessmen or notable personalities passed on, their companies and the organisations they were involved in took out bigger sized condolences to mark the sad occasion.

As odd as it may seem to a generation that has grown up on a digital diet, it’s not uncommon for many Singaporeans who grew up with the newspapers to profess to check on the obituaries section daily.

And in some ways, obituaries serve as a social commentary of a community, as families remember and honour their loved ones who have died. Here’s a look at how obituaries have evolved.

And in some ways, obituaries serve as a social commentary of a community, as families remember and honour their loved ones who have died. Here’s a look at how obituaries have evolved.

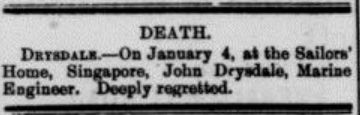

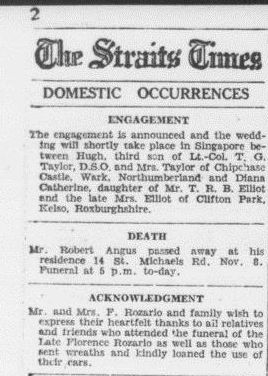

Here’s a copy from 6 January 1910:

A short piece with the name of the deceased, the date of his death, where he died and what his occupation was, as well as a two-word remark that was the equivalent of an expression of sympathy on the passing.

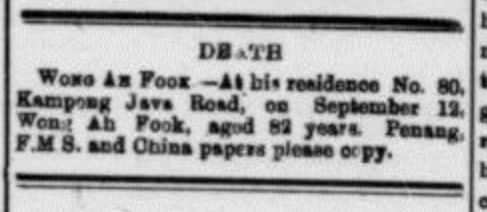

Even the obituary of a notable personality, such as Wong Ah Fook, an immigrant builder and entrepreneur, was very short. Interestingly, there was an instruction for newspapers in Penang and Chinese to copy the obituary.

Wong Ah Fook constructed iconic buildings such as the Victoria Concert Hall in Singapore and the Istana Besar in Johor. He was also one of the founders of the Kwong Wai Shiu Free Hospital in Singapore. Johor Bahru’s main street is named after him.

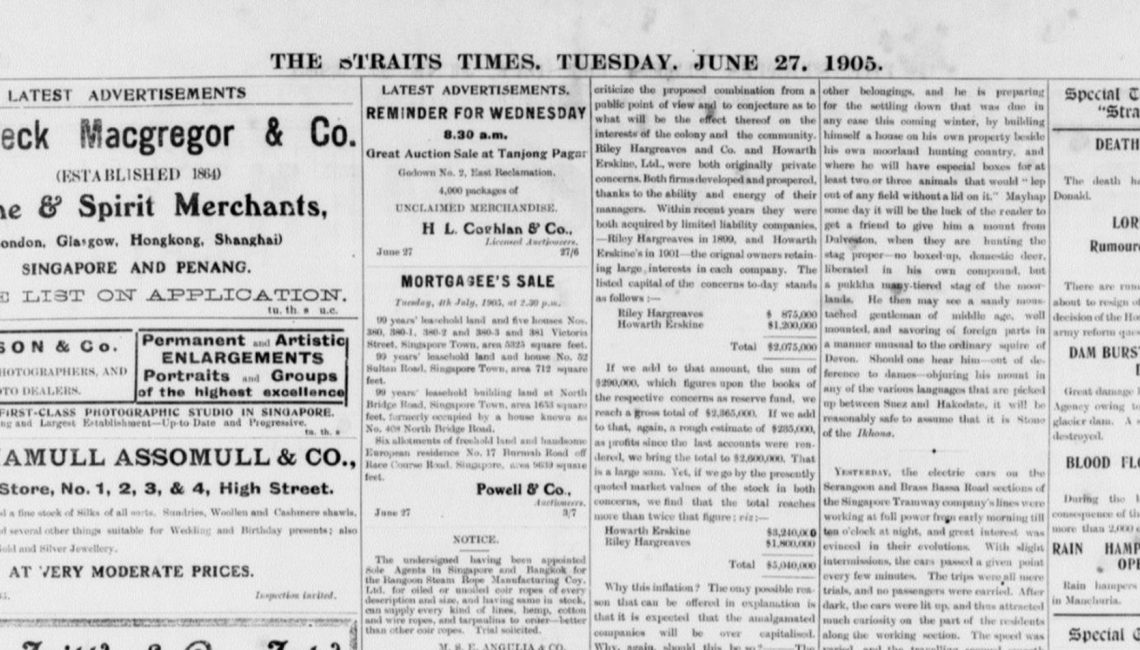

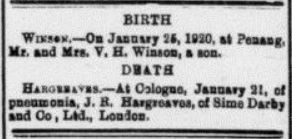

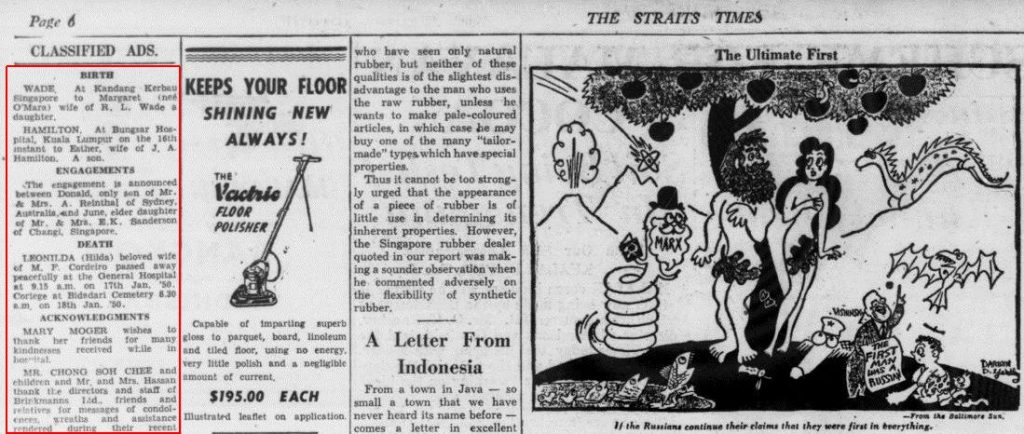

Around the late 1910s and early 1920s, birth and death announcements began appearing together in the same section of the newspapers.

Here is a later obituary, published on 29 January 1920.

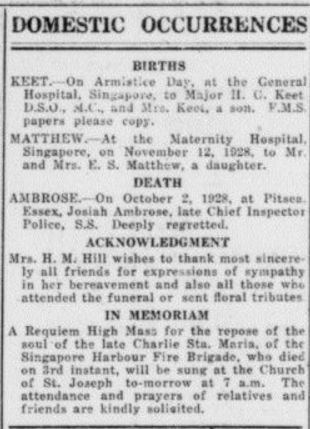

Announcements of life events maintained the same format throughout the 1930s to the 1960s.

From the 1930s onwards, death, birth and marriage announcements were grouped into a section called “Domestic Occurrences”.

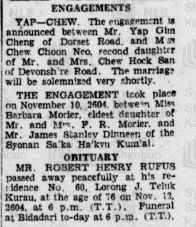

Life and death went on even during the Japanese Occupation of Singapore from 1942 – 1945. Death announcements were published in the Syonan Shimbun from 1943 – 1945, when The Straits Times was not published during the occupation years.

From 1954, obituaries, birth announcements and personals were published with the ad rates displayed at the beginning of each section. The ad rate was $10 for a minimum of 20 words.

During this decade, obituaries revealed more details of the bereaved family, such as how the names of the children and grandchildren.

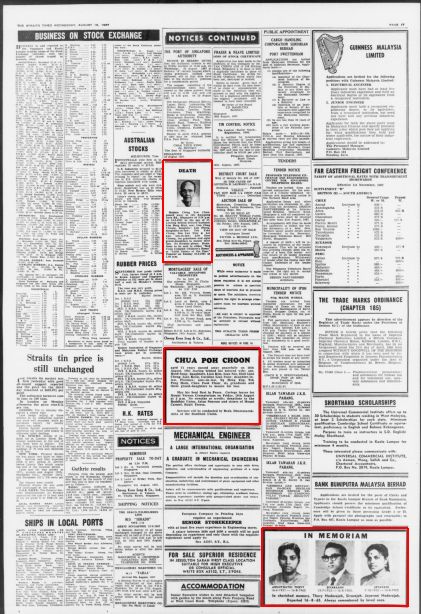

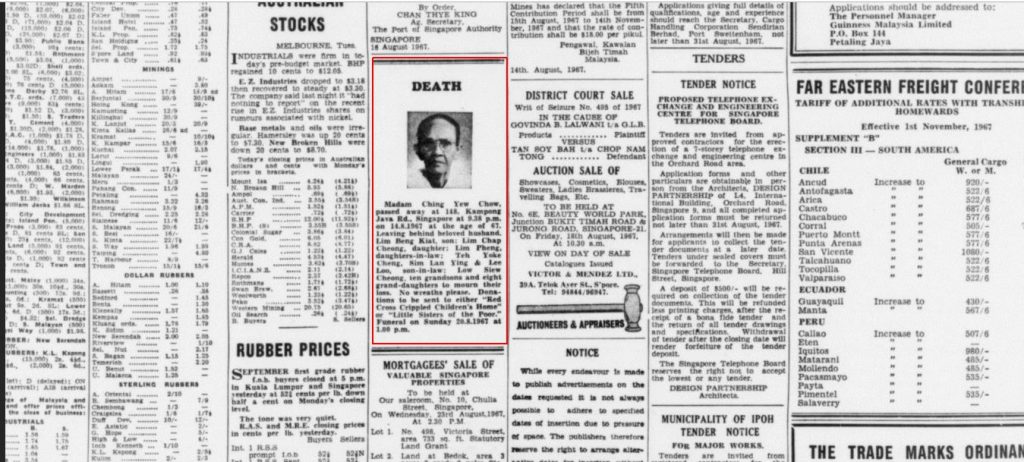

From the late 1960s, obituaries and in memoriam ads were displayed in slightly different formats. A photo of the deceased was published along with the obituary, seen in this edition from 16 August 1967. The ads became bigger and showed up on different parts of the page too.

Sometimes, the ads would reflect the religious beliefs of the family. For more well-to-do families, the ads may also announce that donations received by the family would go to charitable organisations.

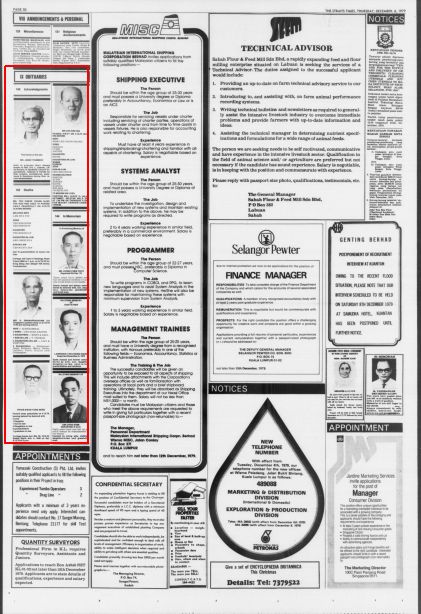

By the late 1970s, the typical format of an obituary that is seen in the papers today can be seen in the personal ads section of The Straits Times.