Longer life expectancies have made it important to have tough but necessary conversations for end-of-life planning. Hafiz Rasid takes you through the process

Talking about death — and by that token, preparing for its eventuality — is, for many, a taboo subject.

Numbers from the Department of Statistics Singapore show that men can now live to an average age of up to 80.6 years and women, 85.1 years. Nonetheless, this longevity can be fraught with challenges. Terminal illness, mental incapacity, or chronic conditions, among other things, can affect a person’s quality of life.

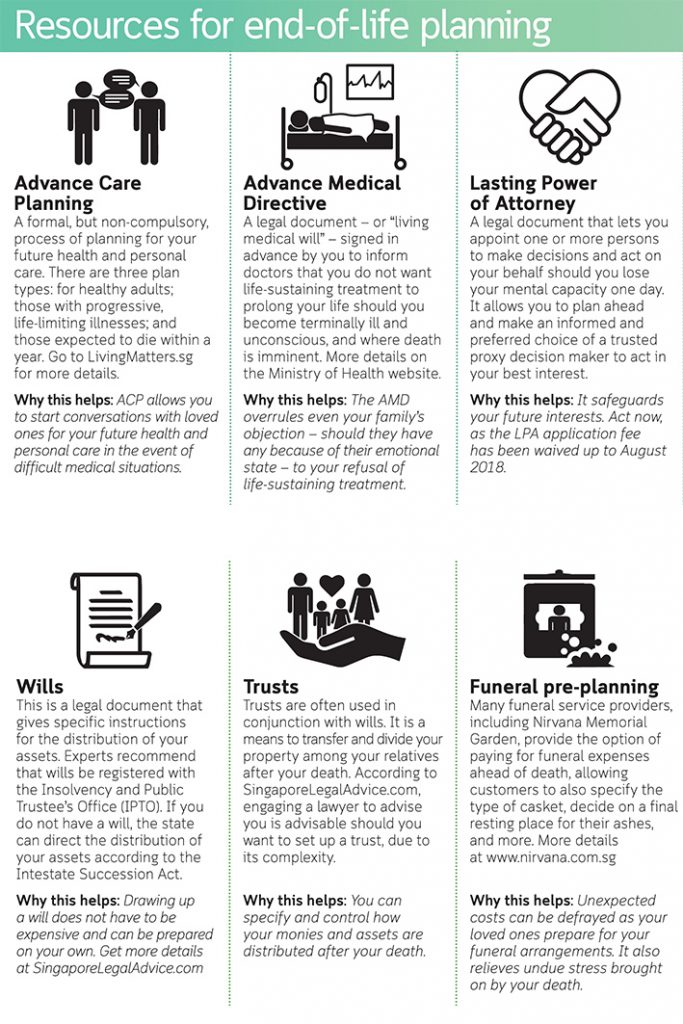

More people are having tough conversations about how someone would like to be cared for as they die, going by the spike of applicants for Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA), a legal instrument that allows a person’s next of kin to act on his behalf.

It rose to 8,360 in 2016 — more than double — from 2,500 in 2014, indicating a strong desire among people to set out their wishes while they are still sound in mind and body.

Instituted under the Mental Capacity Act in 2010 and administered by The Office of the Public Guardian, the LPA lets individuals appoint others to represent their desires if they are mentally unable to function in two broad areas — personal welfare and estate matters.

In the United States and Britain, medical practitioners broach the subject with patients, using questionnaires to guide them in their wishes on how they want to be cared for in the final phase of life.

The Ariadne Labs, a joint centre between Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, US, released an updated Serious Illness Conversation Guide in April this year as a tool to facilitate conversations between clinicians and seriously ill patients about patient values and goals.

In Singapore, Living Matters, the national Advance Care Planning programme (ACP), was started in 2011. Individuals discuss and share ahead with loved ones their care preferences using a set of questions to begin the conversation. This programme was adapted from the Respecting Choices programme at the Gunderson Health System in Wisconsin, US.

Among other things, opening up about the topic of dying allows patients to convey how they want to spend the end of their lives, what kind of medical care they want (and to what extent) in case of terminal illness, health problems or disabilities.

It also allows them to state wishes and requests for how they want their affairs managed, and even details for funeral arrangements.

A healthcare professional says that it is best to make LPA arrangements when the patient is still able to make decisions.

Also remember that the prospective donee must give his consent to be nominated. Talking about LPA can be the start of deeper conversations about the patient’s preferences for future care. The patient’s regular geriatrician or family physician can help to facilitate the discussion.

Proactively making plans for the end gives peace of mind to people, who are assured that their requests and wishes will be heeded.

Mr Eric Ang, 45, an analyst, has already done pre-planning for his funeral and will be looking into settling other end-of-life planning such as Advance Medical Directive and ACP.

He recalls that his father’s end-of-life planning helped to ease the stress that the family already had to go through in his final days.

His father had made arrangements with the funeral home and signed his Do Not Resuscitate legal orders upon being informed by his doctor that his life-threatening medical condition — aneurysm — might worsen.

He says: “My father’s advanced planning definitely made the process smoother and the arrangements were well-coordinated. From personal experience, proper end-of-life planning helps to minimise unnecessary disagreements and ambiguity among family members.”

This article was first published in The Straits Times on Nov 1, 2017